“Puzzles and Politics Under the Sea…”

One of the great boons of the last decade in gaming was the new renaissance for independent game developers. After 2008, when Xbox Live, Steam, PlayStation Network and others began outreach programs to grant smaller studios marketplace access and public exposure, new indie titles flooded the industry. Where the AAA studios often bring high production values, tried-and-proven ideas, and extensive polish to their games, indie outfits tend to be more risky, innovative, and unorthodox with their titles. The challenge for these small studios is always budgeting their time, limited staff, and tinier cash reserves throughout development.

Subaeria, by Montreal-based independent developer, iLLOGIKA, provides a good example of both the unique appeal of modern indie gaming and the unfortunate shortcomings that may follow. It’s a charming action-puzzle game that incorporates light roguelike elements and a unique setting. There’s some clever and fun gameplay here, but the experience is hobbled by technical drawbacks and some glitches.

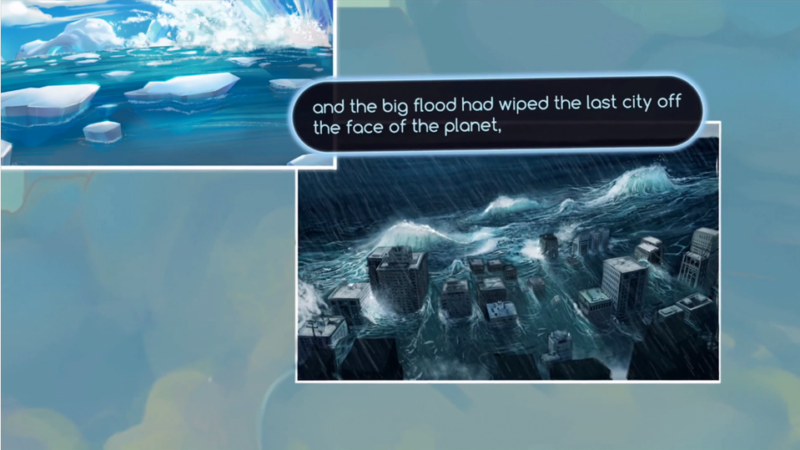

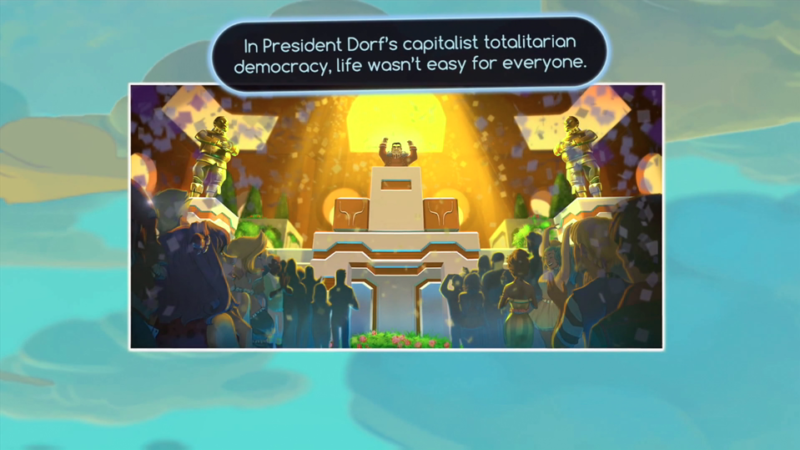

The game immerses itself in a political environment. The story opens in a series of comic-like panels with the aftermath of climate change and its devastating effects on the Earth and human society. Everybody now lives in an underwater supercity called Subaeria. It’s a “totalitarian capitalist democracy,” a term you won’t hear often outside of a political philosophy textbook, much less in a video game. Here, the idea plays out like your standard dictatorship. The city of Subaeria is controlled by a government exerting maximum control over the lives of its citizens in the pursuit of stability and public well-being. Society is stratified into classes, with the lowliest living in ghettos and the highest living in brighter, cleaner, and cheerier accommodations. It’s not a nice place to live if you don’t want the state breathing down your neck, examining your every move for bad behavior. In Subaeria, the punishment for any crime is to be killed (“cleansed” as the city propaganda calls it) along with your entire family. This makes for a grim undersea dystopia, reminiscent of BioShock’s Rapture, but foregoing Andrew Ryan’s extreme individualist vision in favor of something much more Stalinist.

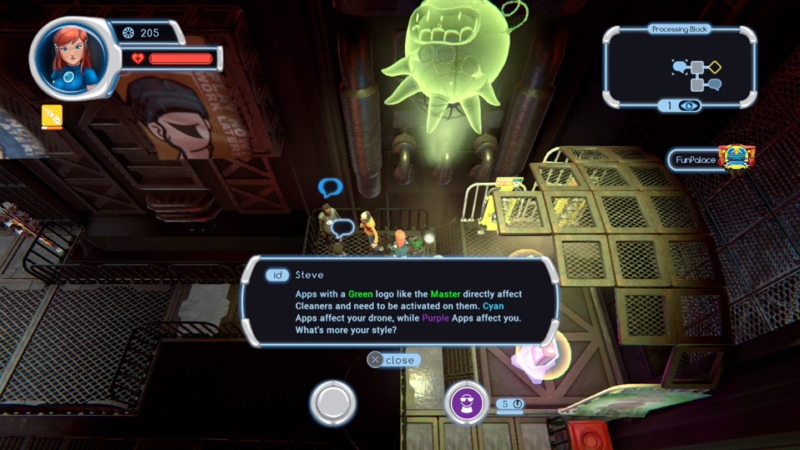

The story initially follows Styx, a young, red-haired girl with a penchant for hacking who loses her family after she’s caught stealing money. She can’t directly harm Subaeria’s robot enforcers (the “Cleaners”), instead you need to manipulate them for her by using a small drone resembling a self-driving vacuum that follows her around. The drone is capable of using several apps you will find scattered randomly throughout the labyrinthine city, each providing different powers. Some apps push objects away from you, grant control over Cleaners, turn you invisible, and much more. Additionally, you’ll do a lot of jumping on top of stacks of crates and leaping across platforms, although the zoomed out camera angle makes judging the height of objects in the environment more difficult than you’d hope. Puzzles revolve around experimenting with the different powers you’ll find to clear rooms of Cleaners. I like this basic gameplay loop, and each room is short and varied enough that the experience doesn’t stagnate too quickly.

The main roguelike elements Subaeria uses are randomized mazes and permanent death, so I get the impression that the developers expect players to fail several times while unlocking more apps and building on their skill and knowledge for their next attempt. The key to a feature like permadeath is to allow the player to jump back in as quickly as possible to reduce the amount of frustration between attempts. Subaeria strikes a nice balance with this early on, even once you’re progressing past multiple mazes it isn’t too draining to die and start the whole journey again from the beginning. As you improve, the next run becomes quicker and easier. There are a few different characters to unlock and several different endings depending on how you play through the game. For a game built around the repetition of playing through randomized variants of the same puzzles and areas, this adds some well appreciated long-term value.

The game is sparing with tutorials. You get a small introduction to the basic controls and concept of using your drone to manipulate cleaners into destroying each other. After that, you mostly need to play the game and experiment your way through the puzzles and new apps you discover. I’m not against a developer putting the responsibility of learning mostly on the player’s back, but there are certainly a few places a little more guidance would save time. Normally, Cleaners can only harm Cleaners of a different color than themselves. Some Cleaners have obvious saw blades jutting out from their sides so understanding how to use them offensively against other cleaners is straightforward. Other Cleaners instead have cannons that shoot projectiles and no saw blades, yet possessing or steering their shots towards Cleaners of opposite colors seems to do nothing. In one instance I ran around for a few minutes during a boss fight trying to figure out how I was supposed to get the cannon cleaners the boss kept spawning to hurt it when their projectiles weren’t working. I discovered by accident that if I used an app that caused them to bounce around out of control they would sometimes ricochet fast enough towards the boss to cause damage on impact. For the most part, the game plays out more intuitively than this, though.

I have to wonder why the game doesn’t show you how the controls are mapped to your controller anywhere. While the controls aren’t overly complex, a simple display screen for them would be appreciated for the game’s quality of life, especially while playing for the first time. A couple of functions, like the lock-on and rolling actions, aren’t communicated to the player outside of experimenting with all the buttons and discovering them yourself.

Subaeria has a nice art style, particularly in the first couple of sections of the game where the city’s dystopian aesthetic is envisioned through ghettos, stores, clubs, and facilities dotted with neon lights and shanty houses built from storage crates and spare materials. It’s a shame that there are so many jagged edges to the environments pulling the presentation down; a greater amount of anti-aliasing would dress the game up nicely. The frame rate also has a hard time staying smooth, giving the action a jittery appearance, and the game will stall for a second if too many visual effects are loading. This was at its worst for me during boss fights, where it’s normal for lots of explosions to go off as bombs and Cleaners detonate. There’s a long load time to endure before a new labyrinth is created when starting the game up. The game occasionally suffers from random crashes, too, which gets ugly if they strike at a particularly bad time, like a boss fight.

Subaeria shows confidence in the design of its puzzles, apps, and boss fights, but the overall package feels unpolished. It looks and performs worse than its gameplay deserves. In its current state, I don’t recommend Subaeria to anybody outside of enthusiasts who can overlook the visual and performance weaknesses. If and when the developers release a patch to address these issues, I would reconsider a positive recommendation.

Score: 6/10

Here is the SUBAERIA Launch Trailer:

Subaeria is available for PC via Steam, Playstation 4, and Xbox One.

PlayStation 4 Review

-

Overall Score - 6/106/10

I've been gaming for 22 years, ever since my mom picked up a secondhand NES, and I've played on just about every gaming platform out there since. I think video games are one of most innovative and artistic mediums in the world today, and I'm always curious how developers will surprise me next.

More Stories

Rayman: 30th Anniversary Edition Review for PlayStation 5

GTA Online this Week Features Continued Lunar New Year Celebrations, Increased Sales for Street Dealers, Biker Bonuses, Plus More

MENACE Review for Steam Early Access