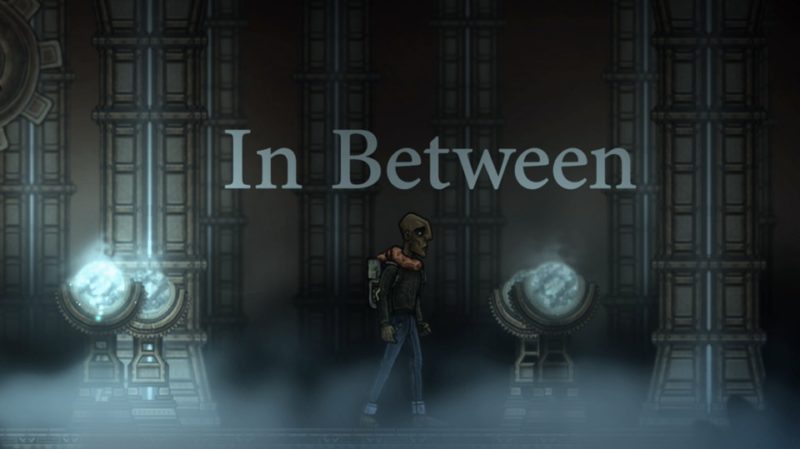

In Between, published by Headup Games, is a puzzle-platformer that wraps itself in a story about a man’s search for inner peace at the end of life. While the game’s puzzles don’t involve controlling time, the narrative weaves itself throughout the protagonist’s life in a manner that makes the sense of time important to the overall atmosphere. Combined with its distinct art style–a curious mix of realism with a slightly cartoon aesthetic set against painted backgrounds–In Between bears something of a resemblance to Braid, developer Number None and Jonathan Blow’s indie hit back in 2008. Much of the gameplay involves manipulating gravity while the protagonist is unable to jump, which also brings to mind Terry Cavanagh’s VVVVVV. Developer Gentlymad has clearly taken inspiration from both games when designing In Between, perhaps a little too much, and it finds itself short of becoming a spiritual successor and serves as more of a humble understudy.

The most intriguing part of In Between is its story: a thread of emotions and recollections examined by a man dying of cancer. He experiences the Kübler-Ross model for grieving, better known as the “five stages of grief,” which serve as the themes for the puzzles of the game. The narrative itself isn’t heavy on exposition or small details but instead focuses on particular moments or scenes from the man’s life to pull on the player’s heartstrings. It’s a quiet, contemplative story that benefits greatly from the voiced narration.

A video game is primarily differentiated from other creative mediums like film, literature, and artwork by its uniquely interactive nature. Video games can communicate with an audience on this interactive level, provoking new thoughts, feelings, and ideas through it in a manner unachievable by other art forms. A game can incorporate beautiful writing, visuals, and sounds but it will never exceed literature, artwork, and film at these things where it always serves as the student instead of the teacher. With this in mind, In Between serves as a important example of how a game can reach for the artful and humanistic but still fall short of greatness because its most important strength doesn’t synergize often enough with the other artistic elements present.

In Between’s puzzles always involve one critical motif: the control of gravity. However, the choice of gravity-based puzzles has no relation to the narrative, which explores nonlinearity of memories and emotion, as well as the challenges involved in accepting one’s mortality. An argument could be made that freely changing the gravity makes literal the biblical saying “turning the world upside-down,” which could then relate to the storm of emotions involved with the protagonist facing terminal illness. However, that argument requires the audience to invent such a hidden meaning when there’s no actual evidence in the game of that particular creative intent. Gravity is then just an interesting gimmick that fuels the gameplay, one that could’ve been replaced with a number of other platforming gimmicks without significantly altering the resulting experience. The problem isn’t that it’s boring to play with but that it doesn’t seem thematically essential or indispensable as an interactive metaphor. A similar issue comes from the numerous puzzles involving pushing boxes around to weigh down switches or provide safe spots to avoid falling into spikes. These types of exercises are so embedded in the history of puzzle games that they undermine the creative innovations of In Between with gameplay that leans on tired conventions instead of inspiration.

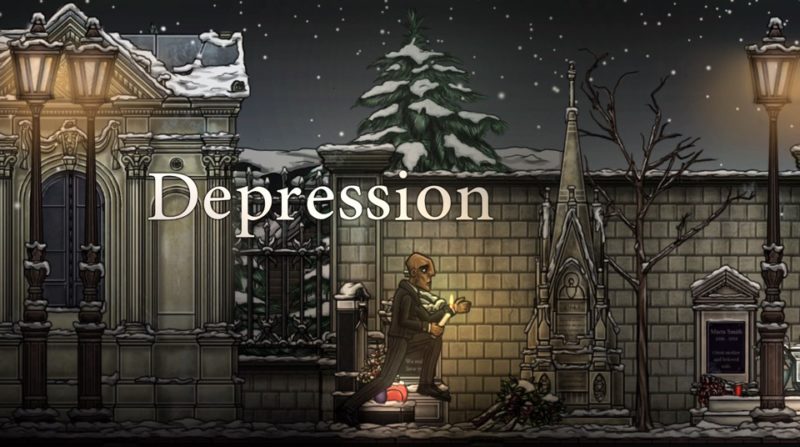

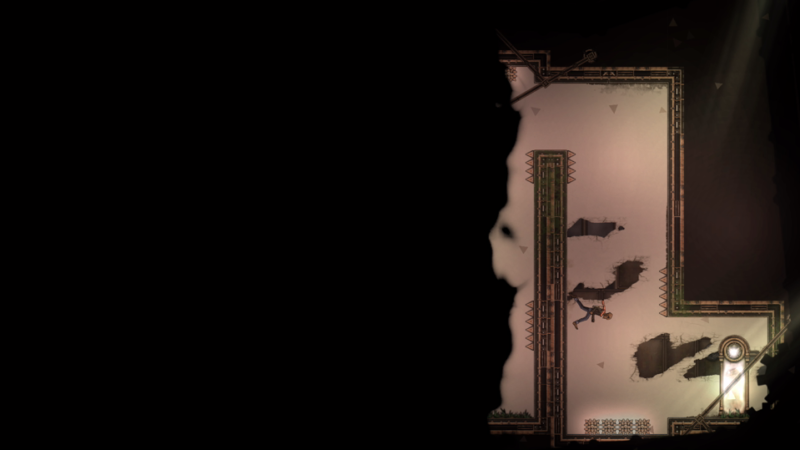

What do work better as inspired metaphors are the physical manifestations of the stages of grief the player navigates alongside the protagonist. Denial involves walls of shadow that slowly close in from the sides of the screen when the player’s back is turned. Anger presents glowing novas of orange light that burn on touch. Depression shrouds most of its stages in cold darkness that freezes the protagonist to death if he strays outside of protective light. Acceptance is less of a metaphor and more of a clever play on game overs in video games to allow the player to conclude the protagonist’s emotional journey.

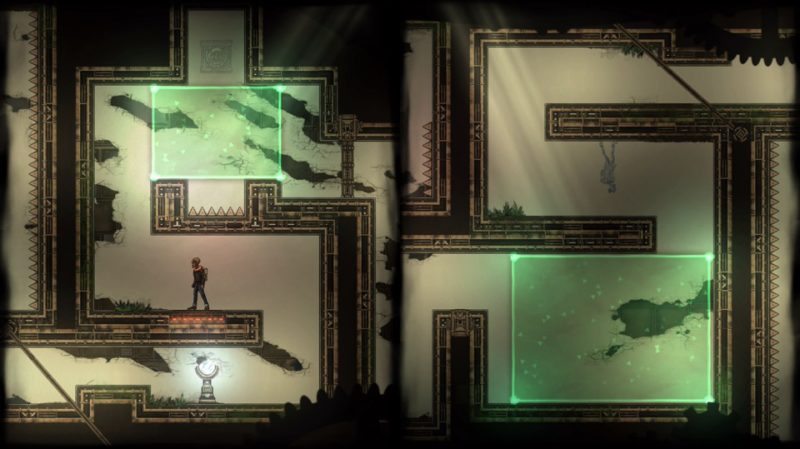

Of particular note is the Bargaining sequence of levels, which splits the screen in half and has the player guide both the protagonist and a vision of his daughter using mirrored controls. The idea of a video game puzzle that requires controlling multiple characters, mirrored controls or otherwise, isn’t new, but the execution is particularly good here. Unlike the Denial sequence that has an enforced timer of sorts due to the encroaching darkness, or the floating hazards in Anger and Depression, Bargaining presents the puzzles and levels in a straightforward manner with the added catch of trying to safely bring two characters together so that they can have a little more time before the protagonist dies. It’s easily the strongest moment of synergy between the artistic vision of the game and its gameplay. The big winner amidst many more “close but not quite” also-rans.

In Between is not a bad game, but it lacks the creative strength and memorability of other games that play with artistic themes and innovations. It’s hard not to recommend Braid over In Between when the former achieves so much more while also being a puzzle platformer that experiments with interplays of narrative, emotion, and gameplay. That said, Braid is decade old at this point, and In Between has at least a few new gems to offer curious players discovering it for the first time as a Nintendo Switch port this year.

7/10

Check Out the In Between Trailer:

Nintendo Switch Review

-

Overall Score - 7/107/10

I've been gaming for 22 years, ever since my mom picked up a secondhand NES, and I've played on just about every gaming platform out there since. I think video games are one of most innovative and artistic mediums in the world today, and I'm always curious how developers will surprise me next.

More Stories

WINDROSE Preview for Steam

Public Test Build for Dead by Daylight’s New All-Kill: Comeback Chapter Now Live

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Splintered Fate Launches New Alopex DLC