Every once in a while, usually from the depths of the indie games sector of the industry, a game of particular quality and uncompromising creative vision emerges. This time around the game in question is more of an encore, but the experience is just as worthwhile the second time. La-Mulana 2 is developer Nigoro and publisher Playism’s sequel to the hardcore cult classic La-Mulana, originally released in 2005 in Japan, remade for the Wii in 2012, and ported to Steam in 2013.

“Hardcore” is a term that gets passed around a lot in the games industry, not just among ordinary gamers but also developers aiming to appeal to a certain demographic. In the case of La-Mulana 2 and its predecessor, the term is used in this review to call attention to how the game forgoes many of the tools and tricks modern game developers utilize to guide players through their games. La-Mulana 2 is content to explain precious little to players explicitly, sometimes even using brief riddles to describe controls for items instead of clear directions. This both works to the game’s advantage by playing off of its sense of danger, mystery, and exploration and also occasionally harms the experience when the developers’ vision of challenging gameplay expands so far as to attack basic user friendliness.

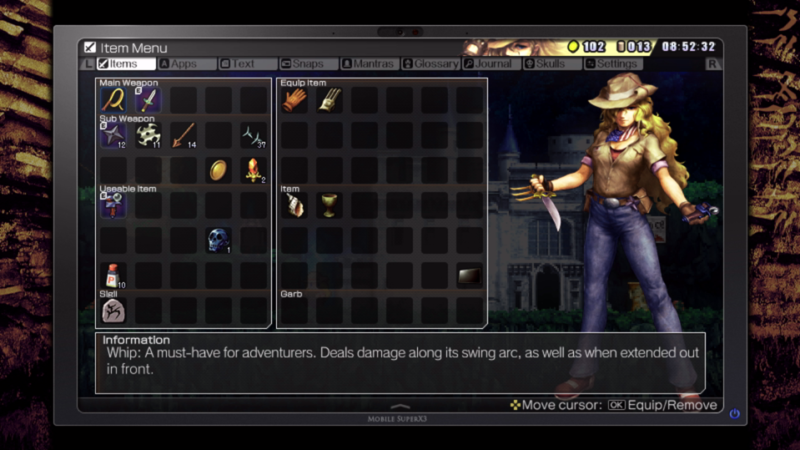

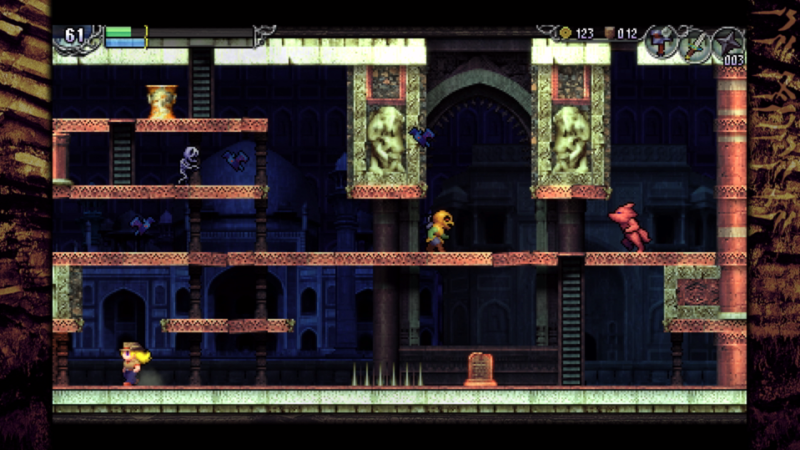

La-Mulana 2 is a platform adventure game, better known to many as a “Metroidvania,” a name that calls back to Metroid and Castlevania (post-Symphony of the Night), two of the major progenitor series that birthed this subgenre. The game is packed full of puzzles and obstacles requiring exploration of a large underworld and acquisition of power-ups. The player starts out fragile but can uncover bonuses that increase their health bar as they explore, and new weapons to expand on the relatively basic combat by adding new tactics for dealing with enemies. New utility items allow the player to unlock new areas as well as examine earlier areas with new capabilities in the search for secrets and previously hidden paths or puzzles.

What gives La-Mulana 2 its hardcore credentials is the way that it requires the player to reason out almost every aspect of the game with only indirect assistance. Even basic controls are sometimes left to the imagination, like with this following case study. The grapple claw item allows protagonist Lumisa to cling to certain walls and surfaces, but how this is done with the controls is left to a semi-vague description about “reaching out with one’s hand.” The answer is that the player needs to hold the Up key (or up on their joystick) while pushing towards the direction of the surface. Once hooked on with the claw, the player can just hold Up until deciding to make Lumisa jump off. This is very simple once understood, but the initial explanation easily leaves players in the position to wonder if the grapple claw isn’t immediately working because the environment is wrong for it, there’s a more complicated means of activating it, etc. This example should make it clear what sort of vision Nigoro is fulfilling here: nearly everything is up to the player to figure out. For puzzles, bosses, navigating levels, and most traps this hands off approach by the developer is refreshing and respects the player’s intelligence. However, the choice to extend this philosophy to even basic functions like the grapple claw’s controls starts to cross over into an affection for obscurity for its own sake.

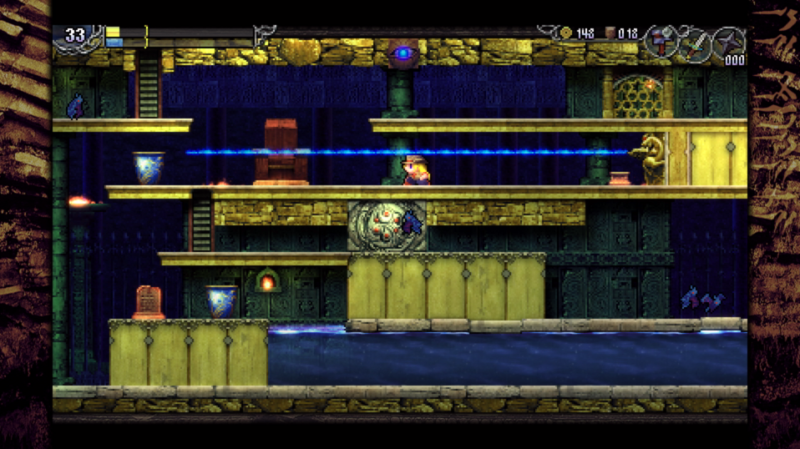

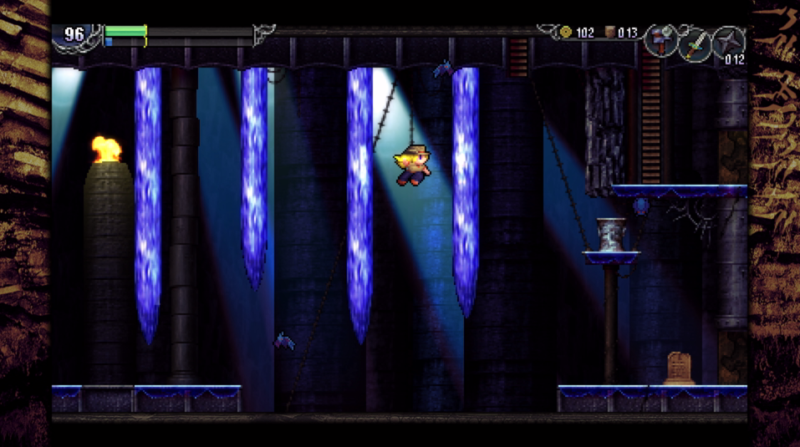

A similar overly affectionate attitude towards difficulty also reveals itself occasionally during gameplay. Most of La-Mulana 2’s traps and puzzles are thoughtfully designed and incorporate some means, often subtle, of alerting the player to potential hazards. A recurring motif is a blue eyeball carved into a wall that watches some intriguing object in the current room ominously; mess with the object and the eyeball zaps Lumisa. Similar traps incorporate other types of warnings that call for close observation and caution while traversing new areas. Sometimes there will be skeletal corpses that can be examined for a hint about trouble ahead. Even with all of this clever design, though, there are still moments where the developers indulge themselves in annoying the player by placing traps that don’t telegraph themselves in any way. The most common version of this is having the floor drop out from under Lumisa’s feet while advancing through a room, usually to little effect outside of inconveniencing and wasting the player’s time. Other times a random part of the floor will drop you into a gap or spikes; you might suspect that the spikes or gap would be the hint of trouble. You’d be correct and incorrect: they’re hinting at trouble, but the gap and/or spikes are wider than the trapped part of the floor and you have no indication for which particular tile is going to drop you, if any. The only way to know is through trial and error, and then making a mental note of it.

You’ll need to make several mental notes because La-Mulana 2 follows the tradition of its predecessor by having a largely unhelpful map that requires unlocking an improvement on it later in the game before giving even basic information like whether you’ve visited a particular room previously or not. This is because the developers appear to hope that players will take the basic shape of their current dungeon (which is all the maps will initially provide) and then proceed to draw their own copy of the map to write in useful notes. This comes across as almost too contrived for the sake of added challenge, and mostly defeats the purpose of providing an in-game map at all, at least until the more detailed version can be discovered much later on. For players who intend to pour their focus and time into La-Mulana 2 continuously without taking too long of breaks this will mostly work fine. But for those who dare to set the game aside for a day or two to do something else or play different games, it’s easy to forget what you were doing and where you’ve been unless you wrote your own notes.

This encouragement to write down real world notes is somewhat odd as the game already provides a system for saving in-game hints provided by messages scattered throughout the underworld dungeons. But the player isn’t allowed to write or add notes to the in-game maps (like where entrances, bosses, and puzzles are) because eventually they’ll unlock a better version that tracks a lot of that stuff for them. So until then the players have to do it themselves, and slowly begin to wonder what the point of this exercise is because it’s a design choice that enforces some early to middle game tedium for no real reason. The starting maps offer almost no information so that the player has to draw their own maps with notes to get a useful map because the note taking system in the game doesn’t allow adding map notes because an improved map will be unlocked and take care of this several hours later. If this sounds like a vicious nitpick, it is, and the design choice in question warrants every bit of it. When one dances in the hardcore fires of La-Mulana 2 everything can be offered up on the altar of difficulty regardless of whether it actually makes the game better for it or not.

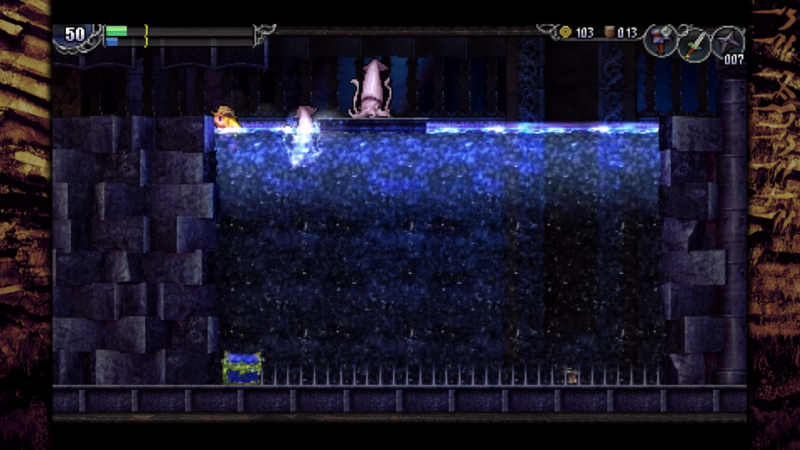

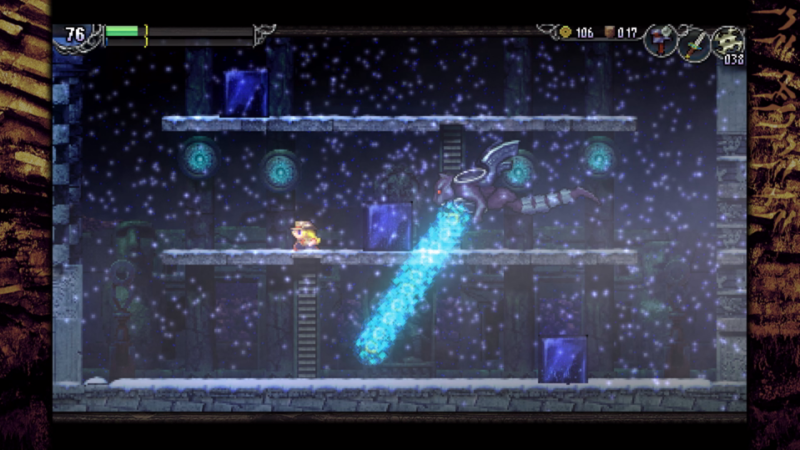

These criticisms aside, the game is a wonderful success in most regards. Platform jumping and combat are both finely tuned systems that demand great precision from players. Lumisa is forced to (mostly) commit to her jumps once she leaps, although some air control is allowed so that she can magically change trajectory mid-flight and do some pretty stylish jumping with practice. Hitboxes tend to be neatly tied to their respective sprites, although some fancier bosses with large bodies can be a little confusing due to some parts of their bodies counting as obstacles while other parts can be passed through like air.

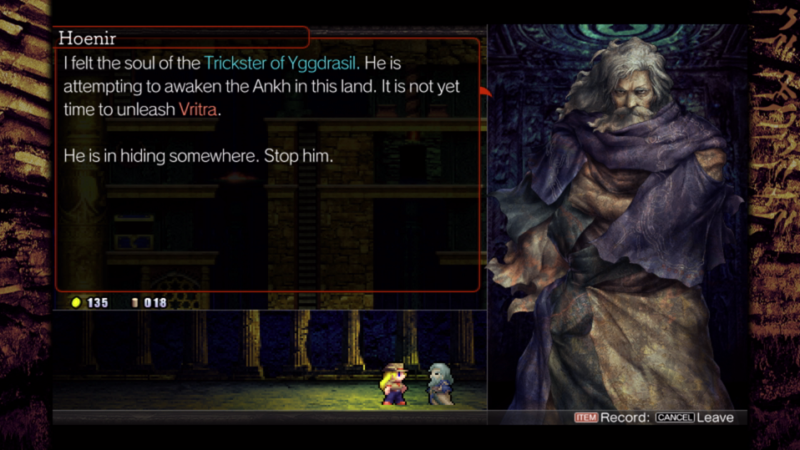

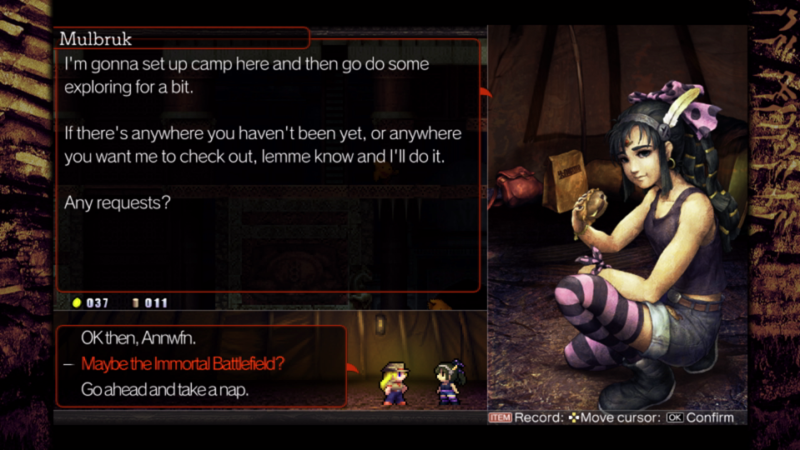

The art style is a beautiful, stylish throwback to sprite artwork reminiscent of the mid-to-late 90’s. Originally, La-Mulana was modeled after old Japanese MSX computer games and their graphics, but the reimagined artwork of the Wii remake, now carried on by the sequel, seems to pay homage to an entire era of gaming rather than the beloved MSX alone. The various dungeons of the game carry their own distinct visual personalities, and the various enemies and NPCs are drawn with an odd but charming mix of sprite art and dramatic character portraits that resemble paintings. Sound effects and musical tracks carry a similar combination of the playful and serious, promoting the sense of adventure and fun but also danger and intimidation.

La-Mulana 2 is far from being a game accessible to most players. It takes pride in its inaccessibility and assumes that the tension and struggle between players and its riddles, traps, and setbacks are worthy goals in and of themselves. The developers have chased this goal far enough that even some basic wisdoms of game design are being challenged. Sometimes to the game’s benefit, sometimes to its detriment. Where nothing is ventured, however, nothing is gained. La-Mulana 2 doubles down on the vision forwarded by its predecessor and it seems little was compromised along the way. It’s a conventional sequel to an ambitious game that dares to assume its players will enter with enough mettle to overcome its challenges without much help, or will gain the mettle to overcome through the struggle itself.

9/10

Check Out the La-Mulana 2 Launch Trailer:

La-Mulana 2 is available on Playism, Steam, Humble Store, and GOG.

PC Review

-

Overall Score - 9/109/10

I've been gaming for 22 years, ever since my mom picked up a secondhand NES, and I've played on just about every gaming platform out there since. I think video games are one of most innovative and artistic mediums in the world today, and I'm always curious how developers will surprise me next.

More Stories

Public Test Build for Dead by Daylight’s New All-Kill: Comeback Chapter Now Live

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Splintered Fate Launches New Alopex DLC

Horizon Journey Review for Steam Early Access